I was delighted when Dr Marianne Dorn, a veterinarian and physiotherapist, got in touch to discuss her work with me. Having listened to my Physioedge podcast with David Pope (http://physioedge.com.au/pe-035-know-pain-mike-stewart-part-1/) Marianne was keen to discuss her experience of working with distressed animals and has kindly written a guest blog to share a vet’s approach to fear, pain and mobility.

Healthcare professionals who work with fellow human beings regularly encounter behavioural and linguistic displays of vulnerability from people in pain. Ben Darlow and colleagues recent work – Easy to Harm, Hard to Heal: Patient Views About the Back (2015) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25811262), reveals such displays.

This characteristic vulnerability that so frequently accompanies pain led Louis Gifford to the formation of his Vulnerable Organism Model. In his 2005 editorial for the Physiotherapy Pain Association’s News publication entitled, The sickness response and the vulnerable organism – When you’re low you hurt more easily (https://giffordsachesandpains.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/issue-19-editorial-vulnerable-organism.pdf ), Louis suggests:

“The notion of a ‘vulnerable organism’ should provide a management opportunity – with the underlying goal for the patient to feel strong, confident and fit and the goal for the therapist being to help get them there. A simple change in mood may be enough – it’s surely a common clinical observation!”

Whilst there are obvious distinctions between human and other animal responses to pain experiences, there are also some striking similarities that highlight our need as healthcare professionals to provide reassurance through the detection of vulnerability, and through skilled verbal and non-verbal communication. This includes touch!

Therefore, it gives me great pleasure to introduce Dr Marianne Dorn’s guest blog.

A Vet’s Approach to Fear, Pain and Mobility

Working in the UK as “The Rehab Vet”, I help restore comfort, confidence and mobility to dogs and cats referred to me with all kinds of orthopaedic and neurological issues. I am forever searching for strategies to understand and help my canine and feline patients, and so was interested to hear Mike’s views on the Physio Edge podcast.

One point that he brought up was the link between fear, pain and reduced mobility in his human patients. Now this is also a key concept for my small animal patients – so I just had to get in touch with Mike and share something of my experiences from the veterinary field.

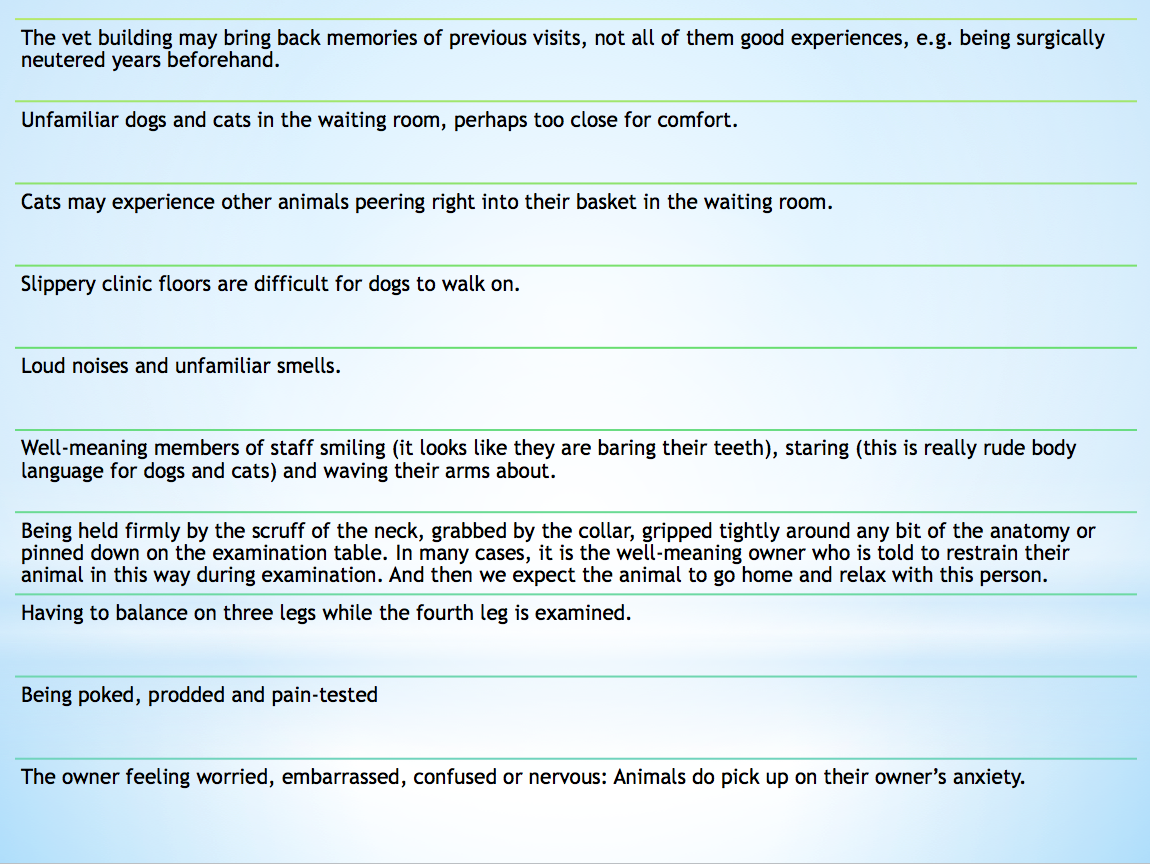

Many pets feel anxious at times, even if their family and health-carers have the best intentions. This is particularly the case in those experiencing chronic pain and/or mobility issues. Just getting around the house and, for cats, negotiating home territory, can become frightening. For dogs, fear of slippery floors and steep steps is a very, very common problem. Unfortunately, visits to the vet clinic cause many of these animals yet more stress for all kinds of reasons.

Before they can begin to feel confident, dogs and cats need to take their own time to “sniff out” the situation. They check for olfactory cues and look about to read the body language of people and other animals when they find themselves in a new situation.

The typical hurried approach within the vet examination room can come across to the animal as quite frightening. Having worked for many years as a general small animal vet, I’m aware that this can be a tense environment, with vets and vet nurses constantly completing tasks against the clock and always ready for the next emergency to come through the door. If the animal reacts to this stress by turning away or wriggling, then they’ll be firmly “held down” or “held still” for examination, and this restraint makes the pet even more frightened.

There’s a further problem for the painful animal who visits the vet clinic. How, as vets, can we know exactly where the animal is hurting? Careful observation and history-taking is extremely useful. But the quickest method is to put the pet through a series of pain tests and, as vets, this is what we have been taught to do. So, for example, a dog that is lame on his right front leg will be firmly restrained while the vet pokes and prods each structure in that limb and manipulates each joint every which way. When the dog flinches or yelps in pain then we have an answer.

Every vet that I have met clearly loves animals, and most are kind, generous people. Vets hate the idea of putting any animal through pain or fear. However, these firm restraint and rapid pain-testing methods are standard practice.

I do notice high muscle tone and awkward postures in frightened dogs and cats. Animals already suffering from musculoskeletal pain will go home feeling worse after a stressful experience, and it is likely that fear may contribute to chronic pain syndromes in pets.

Here are just some potential causes of anxiety for the animal at the clinic:

Subjectively, I get the impression that animals feel less painful once steps are taken to remove the real and perceived threats. Pain-scoring in animals is difficult. I’m going by subtle changes in their posture and body-language and in the way that they react to being touched. What’s more, animals become ready to move in a more balanced and efficient way once the perceived threat has gone. There’s a close connection between fear, pain and mobility.

Things I do to reduce the patient’s fear include positioning myself really carefully when working with them, Tellington Ttouch techniques and careful attention to flooring and to any restraints.

Taking enough time over each session is also helpful. Animals are so used to being manhandled at the clinic that to have a veterinary professional help them into a comfortable position and then just sit quietly with them must come as something of a relief. This also gives me a chance to talk to the owner about how they are coping and to discuss the home care regime.

With plenty of time allocated to each session, I have a better chance of locating any painful areas without forcefully restraining the patient. Initially, I get clues from watching the animal walk, turn, stand and change position. Then I settle the animal into a relaxed position and use my fingers as gently as possible to assess the neck, back and limbs for discomfort, watching for subtle flinching, muscle twitches or gentle behavioural signs (e.g. for dogs, repeated lip-licking) to show that I’ve touched a sore spot.

It’s all very well reducing the stress in the clinic, but what about at home? An important part of my job is to teach owners ways in which they can use their own hands, body position and voice to make their animal feel more comfortable. I also explain something of the animal’s body language to his or her owner, and suggest how they could respond to it. Home visit check-ups offer the opportunity to assess the home and garden environment for causes of stress, from slippery flooring to awkwardly-positioned bedding.

Frightened animals tend to adopt a tense body position, ready for a panicky “fight or flight”. This posture varies between individuals, but often involves a dramatic tightening of the neck and shoulder muscles. Not only is this muscle tightness uncomfortable, but standing like this does not lead nicely into efficient, pain-free movement.

Dr Marianne Dorn BVM&S PGCert SART MIRVAP MRCVS

The Rehab Vet, Herts, UK

Website: http://TheRehabVet.com

https://www.facebook.com/therehabvet

Twitter: @therehabvet